This was the first vacation I’ve taken where I also participated in dowry negotiations. I woke with the sun as usual on Saturday. When the rest of the family was up and about shortly thereafter, Lomilo asked us to bring the sofa set out from the house. We were going to breakfast al fresco and then carry the seating down the road to the church building where Lomilo’s family would be hosting special guests. By now, we were on day four of our pampered-guest routine, so I naturally asked myself, “Who could be more special than us?” A short time later, two of Lomilo’s brothers sauntered in leading a goat and carrying a knife. Alone, a goat might not make a huge impression, but a goat in the close company of a knife surely means that something is afoot, and a few questions later, the picture became clear that a young man of Lomilo’s extended family sought to marry and today was the negotiation for the dowry. The special guests were the young woman’s delegation, coming up from a place near Soroti. Suddenly, there was much to do, and a chorus of relatives trickled in every few minutes. Before long, Lomilo came to me and said, “My brothers say you are the one to slaughter the goat. It is a great honour.” Said brothers had thoughtfully honed the knife well and the process was quick and painless—for me. The animal was quickly butchered and the two halves of the skin and outer muscle stretched across an old bicycle rim atop a modest fire. I was assured that this method of cooking was something of a delicacy and that the brother of Lomilo was the maestro of the leathern steak (a term I have coined subsequent to savouring the provender).

I was bathing when the official contingent arrived, and, peering over the top of the bathing shelter, I could just see that the visitors had come in their own vehicle, something odd to see in Apeitolim, where not one car stays parked. While I finished my toilet, the guests were escorted (or redirected) to the church building where the age-old Ugandan hospitality routine kicked into high gear. Mainly, it consists of showing your respect for your distinguished guests by shutting them into a room by themselves and making them wait for hours as they speculate on what will happen next. Every time I have been hosted by a Ugandan, this has been the norm. Meanwhile, back at the homestead, rice was being cooked, posho mingled, and the well-done-ness of the roasting goat constantly and loudly second guessed. Still not clear on what was happening, I tried to listen in on what Lomilo (who seemed to be stage managing the whole affair) was saying to the assembled men in Ŋakarimojong. He seemed to be delegating different speeches and other official functions, and then he struck on an idea of which I now know we will never hear the end. His brilliant joke was that at mealtime, Chloe should serve the visitors their food both as a sign of great respect to them and, more importantly, an enduing conundrum. With preparations all decided, we sat down and let the visitors sweat it out for another hour or so, and finally the men filed down to the church and made our entrance, I too an enigmatic presence on the team’s roster.

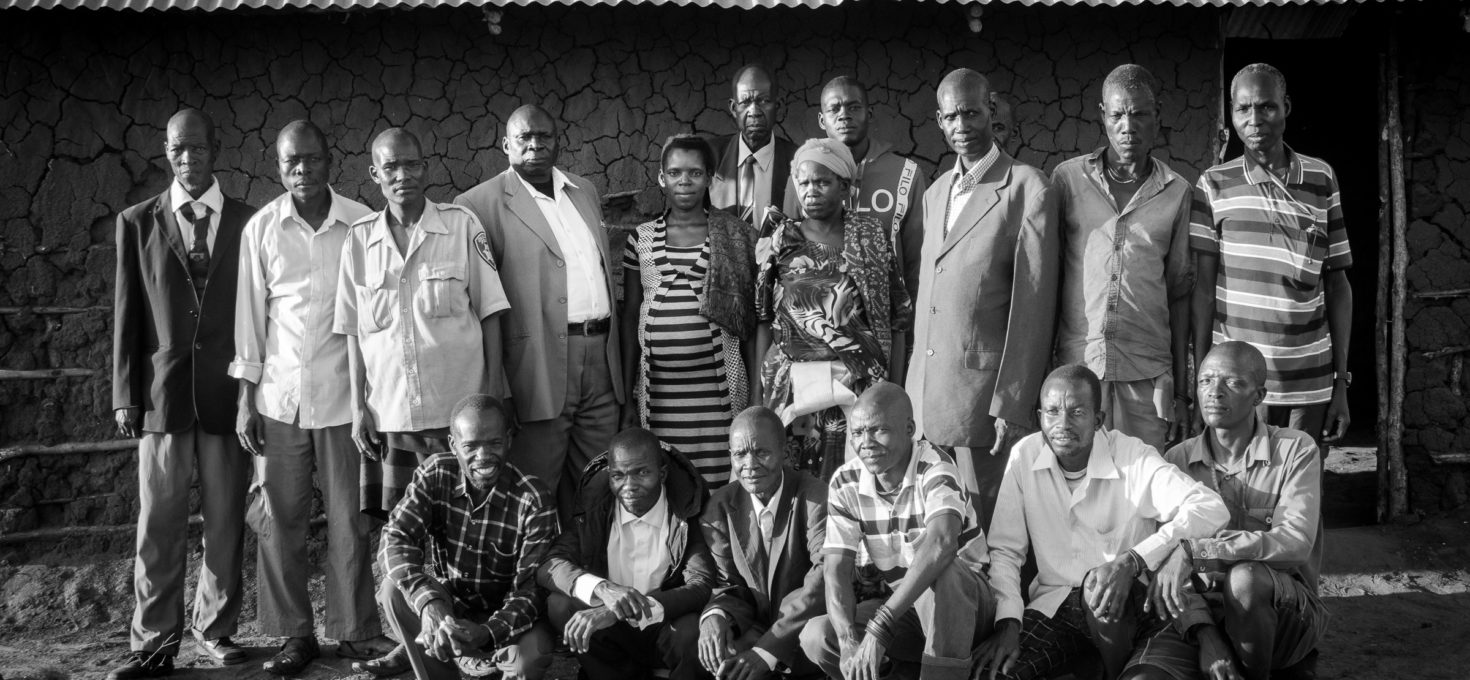

The official programme started with the exchange of pleasantries, introductions, and prayer—all very anodyne. The opposing team contained five men looking sharp in suit-and-ties (and loafers!) and two younger men who, as it turned out, were the hustlers. Our side was all in sandals except one man with a suit and the strangest looking half-knotted tie I have ever seen. Most on our side managed at least a shirt collar, but Lomilo’s brother was in the local blanket and several were in short pants (which is simply not done in any region outside of Karamoja). Our team had already settled on six cows and six goats as a bride price, two of the unfortunate animals wandering about on the roadside all morning, resigned to their utilitarian fate. The pleasantries were short and the opening salvo came early as the bride’s team announced they were going to go outside, write down their offer on a piece of paper (hence the two young hustlers) and forthwith present it to us. It seemed a harmless enough gambit, but our side immediately launched into invective about mistrust and bad faith (I later discovered bad faith is more often than not exactly the plan, hence the impassioned denunciation). Nevertheless, the offer was scribed and returned, and read aloud to those assembled:

- Transportation to the ceremony: UGX 300,000

- Official fee for the local chairman: UGX 50,000

- Member fee for each delegate: 10 x UGX 35,000

- 10 cows

- 15 goats

- UGX 2,000,000 for the parents of the bride

- 1 goat for the grandmother

- 1 goat for the grandfather

- 1 goat for the clan

- A suit of clothes and a dress for the father and mother of the bride

After the reading, it was our turn to exit and confer. As an outsider at an important event, my senses were all on alert trying to read between the lines of what was happening. As we left, there was a palpable exasperation among our members. Rounding the corner, I deduced that this was all posturing. The consensus was that the offer was workable. Again, Lomilo stage-managed the whole affair, assigning speakers and coaching the speeches. We reëntered and started the counteroffer. The substance of it centred around the fact that Karamojong (at least according to our team) do not pay money as part of a dowry. This was a point of cultural contention (or shrewd bargaining) that took the majority of the meeting to resolve. Lomilo’s brother more than once explained that “If our sister marries a man in Kotido, we will not ask money for transport; all of us will walk to the wedding.”

In the middle of the speeches, I was escorted out and given an enormous plate of food which I was told to consume. The circumstances were not clear to me, but I had a sneaking suspicion that my presence was akin to a giant stack of money occupying a chair. Whether this was true or not, I continue to have my doubts, but it was officially explained to me that our hosts were worried that the negotiations would take an excess of time, leaving me famished. As an aside, I have generally become used to eating twice per day maximum, and it is almost a trope that Ugandans eat much more than their American counterparts at a meal. By Saturday, we were three days into the deluge of food that was being prepared for us, so I probably could have have sat at the negotiating table for a full 48 hours before even noticing my stomach “grambling”. In any case, anxious because I was missing an event that realistically I will never see firsthand again, I scarfed the food and dashed back to the church to rejoin my comrades.

By now, we had moved on from the discussion of cash payments to the exact number of animals that could be agreed upon. After much back and forth, highlighted by consistent recriminations by the local chairman of the opposite side against my Karamojong brothers regarding their constant fallback to describing their poverty, the party settled on six cows and ten goats. The young man, present, was admonished to don the tall hat and ostrich feather and go a-begging to every relative he could rustle up to raise the animals. Communication regarding the payment schedule was due in no less than one month.

Having agreed, we closed in prayer, and Lomilo’s coup d’etat went into action as Chloe came to serve the visitors their food. Again, in traditional Ugandan style, we did not eat together, but let the visitors to eat alone while we came back to the compound (where I was forced to eat another plate of food). The whole crew was in high spirits over their grand success, and as the Karamojong are wont to do, the story of the negotiation was hashed and rehashed to much satisfied laughter.

The comestibles ingested, the order of the day was to pray together briefly, and then to wrangle two cows into the tiny bed of the double cab pickup in which the ten visitors had arrived. Either as a specimen of animal cruelty or a metaphor for the upcoming nuptials, the scene was rattling, but the object attained. The truck pulled out onto the road with all its cargo just as the sun dipped below the horizon.

What with all the feasting, there was not much push for an evening meal. Instead, we prepared tea in the gloaming and Lomilo helpfully clarified several facets of the proceedings for me. I had been rather confused about the composition of the two negotiating parties. Obviously, my presence there was understandable as I am now a part of the family, but others seemed out of place. The bride-to-be’s team included a local chairman from their area who, as far as I could tell, was not related to the family in any way. On our side, I was not clear on the young man’s relationship to Lomilo. He was not a brother, not an orphan, and didn’t live in Apeitolim, so I was unclear how Lomilo came to be his champion. As it was explained, each side is allowed to pick their dream team to negotiate the dowry and apparently this man thought Lomilo had the sway and heft to chair the proceedings. The local chairman for the other side obviously had his own interest in the party (see initial offer, point 2, for which he vociferated long and loud), but was also chosen because, being a politician, and a Ugandan politician to boot, he knows how to shout a speech and make his point.

This explanation also raised another question. The one member of the other delegation for whom I could not help but have an appreciation was the girl’s father’s oldest brother. He dressed with a perfunctory elegance and carried himself throughout with a trifle of disdain for the whole proceeding, as if he’d wasted too many days of his life negotiating dowries and already knew where everyone was going to land at the end of the day. Aside from his introduction, he did not speak through the whole proceeding, and in my mind, this gave him an air of wisdom and shrewdness that was less evident in the members who spoke much (there’s a proverb for you). I mentioned this to Lomilo, who thought the man was useless. “You want people standing for you who are willing to act crazy,” was his exact response to me.

As the fire burned down, my friend again recounted his own masterstroke. “Those people have gone home confused,” he said. “They asked me, ‘How have you deceived us that you have little money, yet you were able to hire these whites to come and serve us?” He smiled broadly and admired his handiwork, happy that we had come out on top in the negotiations, but relishing the caper.